Nomenclature in chemistry took a giant step forward in the late eighteenth century when French chemists – Louis Bernard Guyton de Morveau (1737–1816), Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–94), Claude Louis Berthollet (1748–1822) and Antoine François Fourcroy (1755–1809) – proposed a system of names for inorganic substances based on their elemental composition. Sodium chloride for a substance formed from sodium and chlorine, for example. Their Méthode de nomenclature chimique was published by the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris in 1787, and its inspiration clearly was the binomial system for nomenclature of animals and plants that had been introduced by Carl Linnaeus (1707–78) in 1735 and 1753, respectively.

As with most sweeping changes, it took a while for the new names to catch on – copper sulfate for blue vitriol, sodium sulfate for Glauber’s salt, and lead acetate for sugar of lead. There continue to be chinks in the nomenclatural armour, of course, especially for industrial chemicals for which the systematic names are seldom heard: think lime (calcium oxide) and slaked lime (calcium hydroxide).

Reforming organic chemical nomenclature was much more complicated. There wasn’t much progress until the middle of the next century, as I have mentioned in some of my recent Letters. The result was a whole new language, one that we struggled to impart to first-year students but largely ignored in our daily life. As with inorganics, the trivial names for industrial substances proved very hard to displace and even laboratory chemists shunned propanone for acetone. In a kind of ‘Sunday observance’, we used the new language in much of our published work, under the eye of the editorial ‘clergy’, but on weekdays we lapsed. It was only a small transgression to speak of stearic instead of octadecanoic acid, but who would blame us when we eschewed pentacyclo[4.2.0.02,5.03,8.04,7]octane for cubane?

A lot of what started as lab jargon, only to become part of the lexicon is described in one of my favourite books, Organic chemistry: the name game, by Alex Nickon and Ernest F. Silversmith (1987), from which I borrowed the title of this Letter. Most of the names the authors mention have been bestowed in modern times. I don’t think there is an equivalent book about inorganic substances and examples that could find a place in such a book don’t come easily to mind. Perhaps modern inorganic chemists haven’t been so keen to vocabularise.

The field of organometallic chemistry offers many opportunities for the creation of catchy, simple names for complex compounds, a simple example of which is ferrocene (cyclopenta-1,3-diene;iron(2+)). In 1830, William Christopher Zeise discovered a compound of platinum and ethylene; over a century later it was shown to be K[(η-C2H4)PtCl3].H2O, but I’m not sure when it was dubbed Zeise’s salt. In the second half of the last century, coordination chemists produced (and named) crown ethers and cryptands.

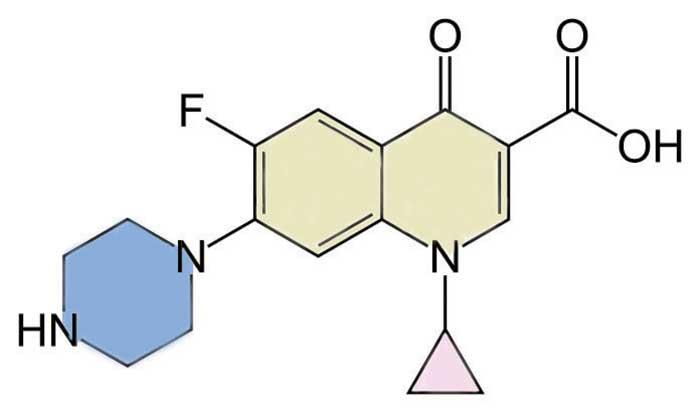

Pharmaceutical companies come up with the simple – and sometimes not-so-simple, but often catchy or even euphonious – names for substances that have long and complicated systematic names. To see how it was done, I set out to see why Ciprofloxacin might have been chosen as the marketing name for 1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-4-oxo-7-(piperazin-1-yl)quinoline-3-carboxylic acid, the structure of which is shown.

Ciprofloxacin is the best-known member of the fluoroquinolone family of antibiotics, all of which contain floxacin as part of their commercial names. None of them include ‘quinolone’ – the structural unit I have shaded in yellow – as a segment in the name, but the one suffix that appears as 4-oxo in the systematic names, is certain to be the source of ox. The other common segments are fl for the fluorine substituent, and acin, which is probably a homonym for azin, taken from the piperazine ring that I have shaded in blue. There are a few members of the fluoroquinolone family that do not contain this structural unit, but it was present in the first of this group to be invented, norfloxacin, and the acin seems to have been carried over for others in which the piperazine has been replaced by other heterocyclic rings. The unique segment in Ciprofloxacin is cipro, probably another phonetic slide, this time from the cyclopropyl ring that I have shaded in pink.

Maybe you didn’t need to know all this – just take the stuff and hope you get better because it could be an example of Bismarck’s warning that it might be best if we didn’t know how laws and sausages are made.