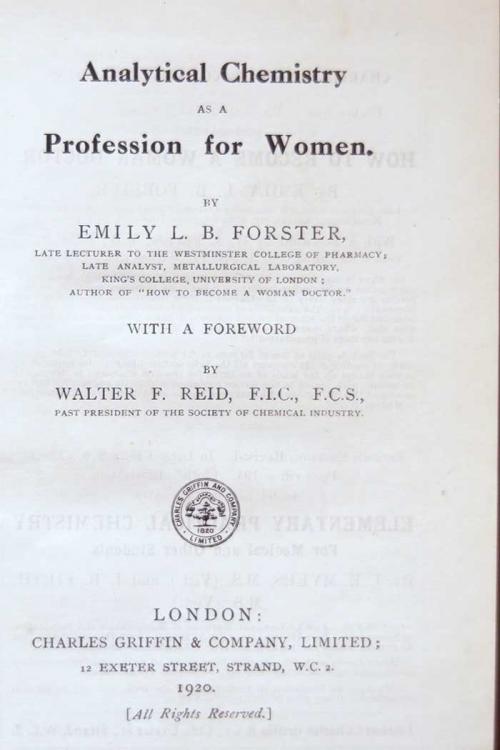

I have a special bookshelf for little volumes. This one, Analytical chemistry as a profession for women, was published in London in 1920. It has 125 pages of size 10 × 16 cm. The author was Emily L.B. Forster, described on the title page as late lecturer to the Westminster College of Pharmacy; late analyst, metallurgical laboratory, Kings College, University of London; and author of How to become a woman doctor. In her preface, Forster says that ‘many women engaged in the somewhat monotonous work of school teaching are turning their attention to “practical” scientific work’, and the foreword provided by Walter F. Reid, past president of the Society for Chemical Industry, writes of chemical control in the industry and the need for qualified analysts, especially women, in this fascinating profession. Forster, writing so soon after World War I, adds another dimension to analytical chemistry in a chapter on ‘Science and Patriotism’. Although they were not in the firing line, women could do their bit for the war effort.

Successive chapters deal with the cost of training, the nature of work in private and government laboratories, self-employment, and the role of the public analyst. The courses available at 24 British universities are summarised, and there are chapters on the Institute of Chemistry (on which the Australian Chemical Institute was modelled, by the way), scientific societies and their libraries. There is advice that would now seem to be patronising, if not actually provocative, in ‘Hints to the Woman Worker’. These are explicitly addressed to the woman analyst as role model in her laboratory, and they cover things like punctuality, tidiness, cleanliness, all apparatus being in its appointed place, and dress that is ‘modest and trim’ although preferably covered by a good dustcoat or overall.

Marelene and Geoff Rayner-Canham have written quite a bit about British women chemists, and they included Forster in their 2008 Chemistry was their life: British women chemists 1880–1949. They have contributed to the extensive literature on gender-typing of science careers, and identified crystallography, radiochemistry and biochemistry as fields where women felt most welcome. Joan Radford, historian of the School of Chemistry at the University of Melbourne, felt that women were most attracted to disciplines where manual skill and attention to detail were important, such as microscopy and analytical chemistry.

Forster was a serial author who began her publishing career in 1917 with How to become a dispenser: the new profession for women. Woman doctor was published in 1918, before Analytical chemistry in 1920. There was a gap until 1926 when Vegetarian cookery was published; then in 1942 a revised and enlarged edition appeared, with a special chapter on wartime food. Before Dispenser appeared, Forster’s article ‘The Ideal Neighbourhood for the Woman Pharmacist’ was published in the Pharmaceutical Journal and Pharmacist in August 1916. A country position would provide broader scope for the work of the pharmacist, ranging from extracting a tooth or poisoning a cat, to attending to a sick cow and gossiping over the counter with the farmer who hoped to save on veterinary fees, Forster observed. However, such a position might not prove congenial for a lady chemist. Seaside towns would provide only seasonal business, and cathedral towns should be avoided because anything new there is looked upon with suspicion. Good choices could be London suburbs where there were clusters of girls’ schools. Wherever she practised, the woman pharmacist with ‘modern views’ might nonetheless need to offer sidelines such as nursery and toilet goods (and possibly, the article seemed to imply, unmentionables) if the business were to survive.

Her books met with mixed reviews. The reviewer of Dispenser said that it contained nothing that could not be gleaned from institutional publicity and that, because of the fees involved in taking the necessary examinations, the profession was unlikely to become over-crowded. In the foreword to Woman doctor, Dr W.J. Fenton, Dean of the Medical School at Charing Cross Hospital, wrote that ‘it contains all the information likely to be required by anyone taking up the study of medicine ... is thoroughly up to date ... and recommended with every confidence as to its accuracy and merits’. On the other hand, an Irish reviewer said that Forster had overlooked the opportunities for studying medicine in Ireland, and that the book was full of mistakes that needed to be corrected before a second edition were published.