The chemical weapons convention (CWC) is one of the most successful arms control treaties in existence. It outlaws the production, stockpiling or research on offensive lethal chemical weapons, and places dual-use chemical industries under a monitoring and inspection program overseen by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

The CWC is a legacy of the end of the Cold War. The collapse of the Soviet Union reinvigorated the long-dormant chemical weapons control. This culminated with most nations signing and ratifying the treaty, which came into force in 1997.

Only four UN recognised nations have not acceded to the CWC. North Korea is widely accepted to have large stocks of various agents. Egypt and Israel both take a ‘will neither confirm, nor deny’ stance, but equally have not agreed to allow monitoring of their industries. Finally, South Sudan has expressed intention to accede, but has not yet done so.

Each nation is responsible for the destruction of its own stockpile of weapons (either alone, or with the help of others), with compliance monitored by OPCW. So far, about 96% of declared stocks of chemical weapon agents have been eliminated, including all of Russia’s declared stockpile.

Yet, chemical weapons have recently been used in state-actor-supported attacks on large (Syrian civil war) and small scales (the murder of Kim Jong-nam and the alleged attempted murder by poisoning of former Russian spy Sergei Skripal in the UK). Fear exists that these incidents may represent a falling back by the world’s governments on the principle that chemical warfare should never occur.

Modern militaries can operate in a chemical or other toxic threat environment (CBRN from chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear), and assume their peers can do the same. This leaves chemical weapons as an anachronism, with only limited offensive value against an enemy of similar technological sophistication.

However, civilians remain vulnerable to attack, either by applying military techniques (Iraq, Syria) or to targeted assassination. Equally, non-state actors have succeeded in producing lethal agents and using them in terrorist attacks (Tokyo).

If the outlawing of chemical weapons is slipping, that may lead to nations attempting to circumvent the spirit of the treaty by developing pseudo-non-lethal agents, or by the offensive use of agents produced under the convention for defensive testing. These issues, often overlapping, leave the convention as it stands facing questions about its relevance as we enter the mid-21st century. As reported in Science (doi: 10.1126/science.aav5129), this is an important opportunity to get some key things back on track.

What is a chemical weapon?

It’s important to clear up a common misconception about the CWC and how it handles lethal chemical agents.

Under the convention, the use of the pharmacological effects (what the chemical does to the body) of any chemical to achieve a military outcome (death or permanent disability) makes that material a chemical weapon.

This means that novel agents, such as the Novichok (or A-series) chemicals alleged to have been used against the Skripals, are illegal, not because of their structure, or mode of action, but simply because they are toxic and someone attempted to use them to kill.

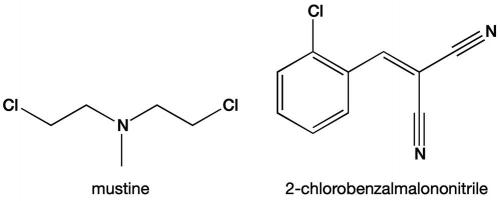

This definition can create some complexities. If we take as a given that many chemicals are potentially lethal – it’s the dose that makes the poison after all – how do you regulate compounds that are likely to be used as weapons? How should these be distinguished from those that could be fatal, but aren’t typically applied for ill-purpose? For example, the anticancer drug mustine – also known as nitrogen mustard – is a schedule 1 weapon under the chemical weapons convention (under the codename HN2), but has also been on the list of drugs that the World Health Organization considers essential for a functional national healthcare system (http://archives.who.int/eml/expcom/expcom15/deletions/Mustine.pdf).

This last thought leads to the potential issue that a country could develop a new weapon, but claim that it is designed for civilian law enforcement.

Police action or short cut to new weapons?

Riot control agents (RCA) are those such as pepper spray, or 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile (better known, slightly erroneously, as CS-gas). These compounds are designed to cause the victim discomfort. The effects of RCA dissipate soon after the victim is removed from exposure – similar to how, if you get capsaicin in your eyes while cutting chillies, you can wash the compound away with lots of water or milk.

These agents are only lightly regulated under the chemical weapons convention. Their use is allowed as part of normal law enforcement, but prohibited in war.

Different from these, incapacitating agents are defined as those that cause the victim to lose consciousness, or otherwise become systemically incapacitated – but the effects of these are not reversible by removing exposure. Examples that nations experimented with before their outlawing include chemicals that cause massive sensory hallucinations and prevent the victim from recognising reality.

There is much debate about the ultimate safety of RCA, but in general they are seen as safe unless incorrectly used. On the other hand, a Russian incapacitating agent is believed to have caused many of the fatalities during the 2002 Moscow theatre siege.

So how can these agents be legal, while the agent used in Salisbury is immediately considered illegal? What is an appropriate level of chemical force that should be acceptable when applied to a person as part of civilian policing?

What level of research into, or stockpiling of, such compounds would suggest the goal is no longer to develop countermeasures, but is part of an offensive chemical weapons program? The CWC was written to outlaw offensive weapons research, but has its success only moved the goalposts?

Responsibility of scientists

Questions about how responsible a scientist is for the use of their work probably go to Fitz Haber and beyond. The 1918 Nobel Prize winner is generally considered the father of modern chemical warfare for his suggestion that the Imperial German Army use chlorine, the first lethal chemical weapon of World War I.

Today there are several questions about how scientists should interact with the world, using their knowledge to educate the public through the media, while avoiding drawing attention to possible misuses of that knowledge (or allowing their messages to be manipulated to cause panic).

Is it a greater good for society for me to explain that nitrogen mustard (from the example above) treats cancer, than the risk that someone will now try to steal some mustine from the oncology clinic to misuse it?

There is also the problem of dual-use technologies. These are techniques that can equally be used to develop a new pharmaceutical or be applied to develop a new nerve agent.

How much regulation of day-to-day research and commerce is acceptable to prevent those who would do us harm having access to materials and knowledge?

In the 20 years since the ratification of the CWC, we have made discoveries and improved access to technologies that may make it easier to create a truly effective improvised chemical weapon.

The CWC has almost reached the initial goal of the signatories – the elimination of chemical weapons. Now the convention needs to move with the times, to prevent backsliding from the prevailing culture that considers chemical weapons to be unspeakably barbaric.