Technology will always win. You can delay technology by legal interference, but technology will flow around legal barriers.

This is a quote from Andy Grove, former CEO of Intel Corporation, who also said: ‘I was glad I liked Chemistry’.

The Federal Court of Australia has recently held that, for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, an artificial intelligence (AI) system could be named as an inventor on a patent application (Thaler v Commissioner of Patents [2021] FCA 879). The Thaler decision has been appealed by the Commissioner of Patents to the Full Federal Court and only time will tell whether the initial Federal Court decision will stand. Perhaps the Full Federal Court will follow the trend in other jurisdictions, such as the UK, the US and Europe, and hold that AI cannot be an inventor.

While an inventor is a creator of an invention, any patent for the invention is usually viewed through the eyes of the person skilled in the [relevant] art (PSA).

One of the principal requirements for an invention to be patentable is that the invention is not obvious; that is, that it possesses an ‘inventive step’. The Patents Act 1990 (ss. 7(2)) states that an invention is to be taken to involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base, unless the invention would have been obvious to the relevant PSA in light of the common general knowledge (CGK) as it existed (whether in or out of the patent area) before the priority date of the relevant claim. The CGK can be considered on its own or together with: (a) any single piece of prior art information; or (b) a combination of any two or more pieces of prior art information that the PSA could, before the priority date of the relevant claim, be reasonably expected to have combined.

Legal case law tells us that the PSA:

- is a skilled, but non-inventive, worker in the relevant field of technology

- knows the CGK in the art

- is well versed in the nature of the problem being addressed by the disclosure of the invention

- could be a team of relevant people.

Therefore, in brief, whether or not an invention is obvious is judged from the point of view of a PSA and in the light of a certain type of information that is already in the public domain at the priority date (the date of first filing) of the relevant patent.

Irrespective of whether or not AI can be an inventor, can AI be considered a PSA?

SYNTHIA™

AI and machine learning are being increasingly used in predictive chemistry and in the design of chemical syntheses. AI was initially used to design synthetic pathways, but its abilities have been expanded to navigate around patented syntheses.

Chematica was one such AI system that was developed in 2012 as a hybrid between a database and artificial intelligence, containing about 60 000 reaction rules entered by scientists. It was renamed SYNTHIATM after it was purchased by Merck KGaA in 2017 (bit.ly/3G12czs).

SYNTHIA can quickly identify viable routes for the synthesis of chemical targets from predetermined starting materials. SYNTHIA can also be used to circumvent chemical patents. The AI system can consider millions upon millions of synthetic pathways (that are considered to constitute prior art information) and find solutions that circumvent patented synthetic methods. The system looks at the key chemical structures and identifies which bonds must be disconnected in accord with the essential elements of the drug patent claims. The AI system then flags these bonds as not to be cut and refers to its database to find alternative synthetic routes.

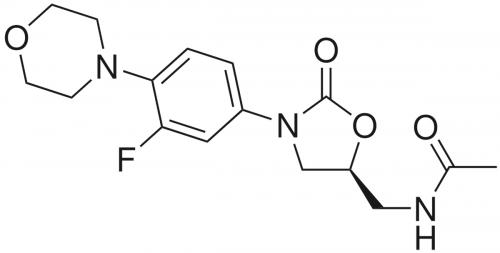

SYNTHIA’s power has been illustrated by circumvention of patents granted for commercial drugs, such as Pfizer’s antibiotic Linezolid, Merck’s diabetes drug Januvia (sitagliptin), and Novartis’ multiple myeloma drug Farydak (panobinostat). For example, for Linezolid, SYNTHIA identified formation of an ozaxolidinone ring as being essential and flagged that the ring should be preserved. Within five minutes, SYNTHIA designed several new synthetic pathways using different starting materials (Molga K., Dittwald P., Grzybowski B.A. Chem 2019, vol. 5(2), pp. 460–73).

Returning to the points outlined above, SYNTHIA would seem to have all four characteristics of the PSA. While its artificial intelligence is currently directed to finding ways around synthetic routes in existing patents, it could be directed to finding the synthetic route in the patent, based on publicly available data that was available at the priority date of the patent.

There are many tests applied by the courts to assessing the inventive step. A well-known test from the Wellcome Case is summarised as follows:

The test is whether the hypothetical addressee faced with the same problem would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from the prior art to the invention, whether they be the steps of the inventor or not.

(Wellcome Foundation Ltd v VR Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd (1981) Pty Ltd (1981) 148 CLR, 262 at p. 286)

Is it fair to ask if SYNTHIA, given the problem that the inventor faced at the priority date, would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from prior art databases to the invention?

This raises interesting questions for patent infringement or validity suits. SYNTHIA cannot appear in court, swear an oath and answer questions posed by a barrister (at least, not at the moment). However, SYNTHIA may be a key tool in the hands of expert witnesses. SYNTHIA could be notionally put in the place of the PSA, given publicly available data available at the patent priority date, and asked to generate synthetic routes that address the problem that is allegedly being solved by the patent-in-suit. The resultant output could provide evidence that the synthetic route claimed in the patent would be one that a PSA would find obvious and arrive at as a matter of routine.

Is it appropriate for AI to become a de facto PSA? If so, would a decision on the grounds of obviousness be justifiable based on a solution identified by AI – a solution that may have been beyond the abilities of a human being? Given the processing speed of AI, will any combination of information available in public databases now become obvious?

It is possible that SYNTHIA will one day be able to contribute her own comments in response to these questions.