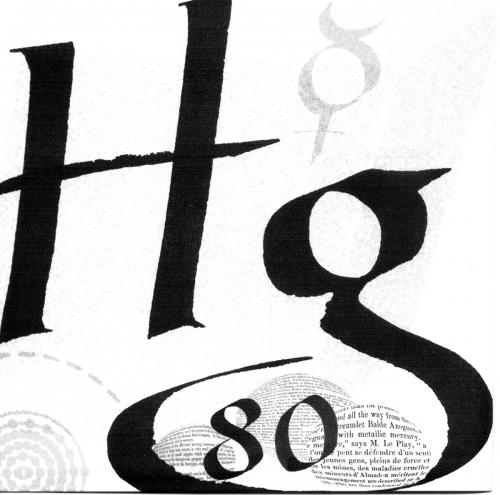

Mercury, the only metal that is liquid at room temperature, exerts an eternal fascination. Its symbol Hg comes from the Latin hydragyrum; literally, ‘water-silver’. That is just how it appeared to my brothers and me as children when we chased the shining drops from a broken thermometer across the kitchen table, fruitlessly trying to pick them up with our fingers.

Mercury’s fascination continued for me in high school, where my friend Dennis and I were looking for experiments to do with a bottle that we had ‘borrowed’ from the school’s chemistry store. Guided by an ancient textbook, we floated coins on it, dissolved aluminium in it, made a rocker switch with it, and even built our own polarograph. We also found that it is the only element to have made an appearance in a Shakespearian play.

The play concerned is Measure for measure. It features a dissolute ne’er-do-well called Pompey and a brothel-keeper called Mistress Overdone. ‘She hath eaten up all her beef’, says Pompey of Mistress Overdone ‘and she herself is in the tub.’ The textbook’s author told us primly that the tub was a bowl of heated mercury, whose vapours were thought to help cure venereal disease when the private parts of the sufferer were exposed to it.

We giggled in our prepubescent way over the picture that this evoked, but knew enough about the dangers of mercury poisoning to avoid heating our own sample. It was our English teacher who had told us about these dangers, saying that the mad hatter in Alice in Wonderland would most likely have had brain damage from the mercury compounds used in the making of felt hats.

Our science teacher seemed less concerned with such dangers, or he would not have had us using a blowpipe to heat red mercuric oxide in a hollow on a charcoal block until it turned into silvery droplets – an experiment that is fortunately no longer on the school curriculum. Nor would he have had us collecting up spilled mercury with a home-made gadget that consisted of a teaspoon bowl cut longitudinally in half, with each half brazed to one arm of a pair of tongs.

I went on to a research career where my very first paper described an unusual use of mercury as a liquid piston in a pump designed to collect and concentrate gases. Sadly, Dennis could not share the excitement of my first publication. Having survived our encounters with mercury and other dangerous substances that we had accumulated in our home laboratories, he succumbed to a melanoma in his early twenties.

Melanomas are still one of the most dangerous forms of cancer, and the search for effective treatments continues. I recently came across a paper where mercury-based compounds have been shown to be effective in treating some types of cancer. It’s early days, but maybe, just maybe, the eternal fascination of mercury will one day offer up yet another prize – this time a real medical one – to its devotees.