I suspect that few Australian chemistry teachers have heard of American chemist Ira Remsen. Last year, after presenting a paper on Remsen at the RACI National Centenary Conference and reading Ian Rae’s piece in the October issue of this magazine (p. 41), I wondered what information concerning Remsen would be useful to Australian chemistry teachers and their students. This year’s February cover of Chem 13 News (https://uwaterloo.ca/chem13news), featuring ‘Beautiful copper solutions: products of a Remsen demonstration’, prompted me to write. Remsen’s story may also be found in US chemistry textbooks, so many North American chemistry students will become familiar with Remsen’s name. Perhaps he and his chemical achievements should become more familiar in Australia. Ira Remsen was born on 10 February 1846. Due to the death of his mother when he was eight, Remsen lived with his maternal great-grandparents. When he was 12, Remsen’s father, who lived in New York, brought him back from the country and Remsen entered the Free Academy of New York at the early age of 14. He was not happy there and he left after a year, so his father apprenticed him under a homeopathic physician to learn medicine. He enjoyed chemistry but accepted his father’s ruling that he should become a doctor. He obtained his MD degree in 1867 at the age of 21, but never really felt settled in medicine. He left the US in the summer of 1869 to study under Justus von Liebig in Munich, but Liebig was about to retire, so he spent a year at Munich studying under Jacob Volhard. He then moved to study organic chemistry at Göttingen under Rudolf Fittig. He was awarded a PhD in 1870.

Fittig moved to Tübingen and Remsen then worked as Fittig’s assistant for two years, gaining further laboratory experience. He returned to the US in spring 1872, where he obtained a position as Professor of Physics and Chemistry at Williams College, Massachusetts, which was poorly equipped for practical chemistry. During his tenure at Williams College, he set up a laboratory for himself and continued his research work in organic chemistry. He became well known as an active chemist for his research and practical ability.

In 1876, Ira Remsen was appointed as Professor of Chemistry at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he set up a department based on the German model. In 1901, he became President of Johns Hopkins University but continued his chemical research and teaching as far as time allowed, until his retirement. Remsen was an enthusiast for student practical work, so he wrote two student practical manuals to accompany two of his texts. He started the American Chemical Journal, in 1879 which under his editorship became the leading journal for chemical research.

Remsen’s influence on emphasising laboratory-based university research in the US based on his German experience became translated into the emphasis for practical work in US secondary schools. This was due to his influence on the Committee [of Ten] on Secondary School Studies (1892), headed by Charles W. Eliot.

Remsen received many honours. He served as President of the American Chemical Society (1902), the Society of Chemical Industry (1910), the National Academy of Sciences (1907–13) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1903).

He resigned as President of Johns Hopkins University in April 1912 due to ill health. During his presidency, he expanded Johns Hopkins University both physically and in reputation. He ensured that women were admitted to the Johns Hopkins courses. He also gave time to public life, serving on the Baltimore Sewage Board for many years as he considered public health issues important. He always regretted leaving research in chemistry for administration. The story of his visit to the antipodes can be found in Chemistry in Australia (October 2017, p. 41). Prior to his retirement, Remsen had refused to work for private industry, but after retirement, he was retained as a private consultant for Standard Oil until his death. Remsen did not retire completely until his 80th birthday in 1926. He died in Carmel, California, on 4 March 1927. After his death, the newly completed chemistry building was named after him and his ashes were interred behind a plaque in the building.

Action of concentrated nitric acid on copper

The story about Remsen and the action of concentrated nitric acid on copper is a favourite experiment for US educators, which happened during his introduction to chemistry at the homeopathic physician’s office. This seems to be where Remsen’s love for chemistry was born.

As Remsen related in one of his many addresses in later years: ‘While reading a textbook of chemistry, I came upon the statement “nitric acid acts on copper”. I was getting tired of reading such absurd stuff and I determined to see what this meant ... The spirit of adventure was upon me. Having nitric acid and copper, I had only to learn what the words “acts upon” meant ... In the interest of knowledge, I was even willing to sacrifice one of the few copper cents then in my possession. I put one of them on the table; opened the bottle marked “nitric acid”; poured some of the liquid on the copper; and prepared to take an observation. But what was this wonderful thing I beheld? The cent was already changed, and it was no small change either. A greenish blue foamed and fumed over the cent and over the table. The air in the neighbourhood was disagreeable and suffocating. How should I stop this? I tried to get rid of the objectionable mess by picking it up and throwing it out of the window, which I had meanwhile opened. I learnt another fact – nitric acid not only acts on copper but it acts upon fingers. The pain led to another unpremeditated experiment. I drew my fingers across my trousers and another fact was discovered. Nitric acid acts upon trousers. Taking everything into consideration that was the most impressive experiment I ever performed. … It resulted in a desire on my part to learn more about that remarkable kind of action. Plainly, the only way to learn about it was to see its results, to experiment, to work in a laboratory.

(Getman F.H. (1940). ‘The life of Ira Remsen’, Easton, Pennsylvania: Journal of Chemical Education, pp. 9–10)

This experiment described by Remsen has become very popular in the US, though now very much modified from the description that Remsen gives, perhaps with the intention of making students as interested in chemistry as Remsen was. More complex experimental variations on Remsen’s simple experiment continue to the present time (Sytsma T.M., Li A., Ganske J.A., Chemical Educator, 2018, vol. 23, pp. 58–63) with the authors acknowledging that the original experiment had ‘visually inspired generations of chemists’.

Discovery of saccharin – serendipity in science

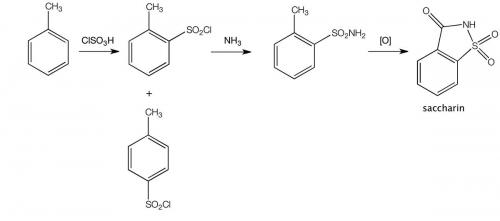

One remarkable incident early in Remsen’s research career concerned the discovery of the sweetener saccharin (o-sulfobenzoic imide, o-benzosulfimide) by his research assistant Constantin Fahlberg. There is controversy about Fahlberg’s conduct in failing to credit Remsen as joint discoverer and for patenting the discovery in his own name. A version of events favouring Fahlberg follows:

Fahlberg was asked to study the oxidation of certain coal-tar derivatives known as toluene sulphonamides, purely because this had not been done before. It seems Fahlberg was a pretty sloppy chemist, usually not even bothering to wash his hands after leaving the laboratory. And that turned out to be his stroke of luck! One day, at dinner, Fahlberg noted that a slice of bread he had picked up tasted unusually sweet. He traced the sweetness to a substance he had been handling in the laboratory and immediately brought this chance discovery to the attention of Remsen.

(Schwarcz J. (2002). ‘Saccharin, and the sweet smell of chemistry: [Final Edition]’ The Gazette [Montreal, Quebec] 23 March)

In this version of the story, much of the credit lies with Constantin Fahlberg, but Fahlberg patented the discovery claiming that it was entirely his own work and as a result he made a fortune! Remsen was annoyed that Fahlberg gave him no credit for the discovery. Remsen considered that saccharin was discovered during an investigation undertaken by Fahlberg at his suggestion and under his direction; the synthesis was first described in a joint paper by Remsen and Fahlberg. In one outburst showing his annoyance at Fahlberg’s actions, Remsen referred to Fahlberg as a ‘scoundrel’.

There are numerous alternative versions of the same story and alternative views about Fahlberg’s conduct. In this version of the story, Fahlberg appears less unreasonable. Fahlberg was an experienced qualified Russian chemist, who had been hired by a Baltimore business, H.W. Perot Import Firm, to analyse a shipment of sugar, testing it for impurities because it had been seized by the US Government Customs service. H.W. Perot also hired Remsen’s laboratory to allow Fahlberg to carry out his experiments. After completing his analysis, there was a waiting period before the trial and Fahlberg obtained Remsen’s permission to carry out his own research in the laboratory. As he got on well with other researchers, he took part in Remsen’s research agenda.

One night that June, after a day of laboratory work, Fahlberg sat down to dinner. He picked up a roll with his hand and bit into a remarkably sweet crust. Fahlberg had literally brought his work home with him, having spilled an experimental compound over his hands earlier that day. He ran back to Remsen’s laboratory, where he tasted everything on his worktable – all the vials, beakers, and dishes he used for his experiments. Finally, he found the source: an overboiled beaker in which o-sulfobenzoic acid had reacted with phosphorus(V) chloride and ammonia, producing benzoic sulfinide. Though Fahlberg had previously synthesised the compound by another method, he had not had any reason to taste the result. Serendipity had provided him with the first commercially viable alternative to cane sugar. Fahlberg and Remsen published a joint paper on their discovery in February 1879. Remsen had a personal disdain for commercial ventures. However, Fahlberg aggressively pursued the commercial potential of the new compound. He named it ‘Fahlberg’s saccharin’ and patented it without informing Remsen, infuriating him.

(Khan M.M., Islam R. (2017). Zero waste engineering: a new era of sustainable technology development. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Scrivener Publishing LLC, p. 369)

Fahlberg put in time, effort and ingenuity in adapting the laboratory preparation of saccharin into a successful industrial process. It is very unlikely that Remsen would have spared the time to do this. Nonetheless, Remsen remained bitter about the discovery of saccharin. It is ironic that a substance that provided intense sweetness could be the cause of such bitterness. The rights and wrongs of Remsen’s and Fahlberg’s actions in the case of the discovery of saccharin would make a good topic for student discussion and debate. The debate could expand into the health issues concerning sugar, which are currently a significant health issue, and the role of saccharin in replacing sugar.

Captivating chemistry

The reaction between copper and nitric acid is a vigorous chemical change. Remsen as an adult remembers his excitement as a young man at experiencing this reaction. This illustrates how chemistry can captivate students for life. The saccharin story illustrates the problems of crediting individuals with scientific discoveries. Searches of the literature reveal that some authors credit Ira Remsen with the discovery of saccharin while others credit Constantin Fahlberg. Most commentators credit both men with the joint discovery of saccharin.