Chemistry is at the heart of the solutions to many global challenges, including the increasingly pressing challenge of plastic pollution. However, it is how the world works together to adopt new chemical technologies that makes the difference.

We need interdisciplinary physical and social science, connected to policy and diplomatic efforts at national and international levels to achieve systemic change – this is science diplomacy.

Here, we describe the science diplomacy already occurring to address plastics pollution, and to perhaps stimulate thought as to how chemists can contribute further to this work.

The ubiquitous nature of chemistry means that chemists are often closely involved with the strategic and diplomatic interactions that go well beyond scientific research. Science and chemists have had a key role in defining and measuring problems as they arise, and connecting with communities and policymakers to build momentum for action.

If an issue is sufficiently serious, genuinely of global concern, and voluntary action has been insufficient, the solution may be to develop a multilateral treaty, which places legally binding obligations on the countries that sign up to it. Prominent examples are the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, the Chemical Weapons Convention preventing the use of chemical weapons and the Antarctic Treaty on the protection of the Antarctic region.

To get a treaty right, science diplomacy needs to drive cross-disciplinary connections and build broad expertise. Science diplomacy is key to ensuring that:

- negotiators build policy and legal frameworks to solve problems that account accurately and effectively for technical limitations and opportunities

- scientists undertake research and develop advice that supports the development and implementation of effective legal and policy frameworks

- both negotiators and scientists build their competency in communicating with one another and other stakeholders.

This involves establishing mechanisms to drive international and cross-disciplinary collaboration, including for sharing resources and knowledge, managing compliance and measuring progress against objectives.

The plastics revolution – the commercial production of synthetic plastics – began in the early decades of the 20th century. In the post-World War II period, there was an explosion of plastic use when plastic replaced more expensive glass, paper or metal in myriad consumer items, often designed to be ‘disposable’.

Plastics pollution has now become an international problem due to increasing global plastic use and production. In 2015, plastic production reached 407 million tonnes per year. By 2050, this is expected to grow to 1600 million tonnes per year. Almost all the plastic ever produced is still in existence, and much of it ends up in natural environments. About 14 million tonnes of plastics are discharged into the ocean every year. Most (80%) of the plastic in the sea originates on land, and the remainder comes from sea-based sources such as ships and debris such as fishing nets.

Once in the sea, plastics destroy habitat, and wildlife swallow plastic, mistaking it for food, or become tangled in discarded nets that continue to fish (‘ghost’ fishing). Marine debris (of which 92% is plastic) affects more than 800 species of fish, marine mammals and birds worldwide. On current projections, about 99% of seabirds will have ingested plastics by 2025, and plastics in the sea will outweigh all the fish by 2050.

Plastics pollution may also be harmful to human health. Plastics may carry toxic pollutants, and some microplastics have been shown to carry carcinogens, mutagens and reproductive toxins. Humans currently swallow up to 52 000 microplastic particles each year in their food and drink.

As well as threatening our health, wildlife and ecosystems, marine plastic litter threatens our livelihoods. Deloitte estimates that marine plastic pollution resulted in economic losses of US$6–19 billion (about AU$8–25 billion) for 87 coastal countries in 2018. This is largely due to impacts from fishing, trade and coastal tourism, which are critical to the prosperity and economic resilience of coastal states such as Australia and our Pacific Island and South-East Asian neighbours.

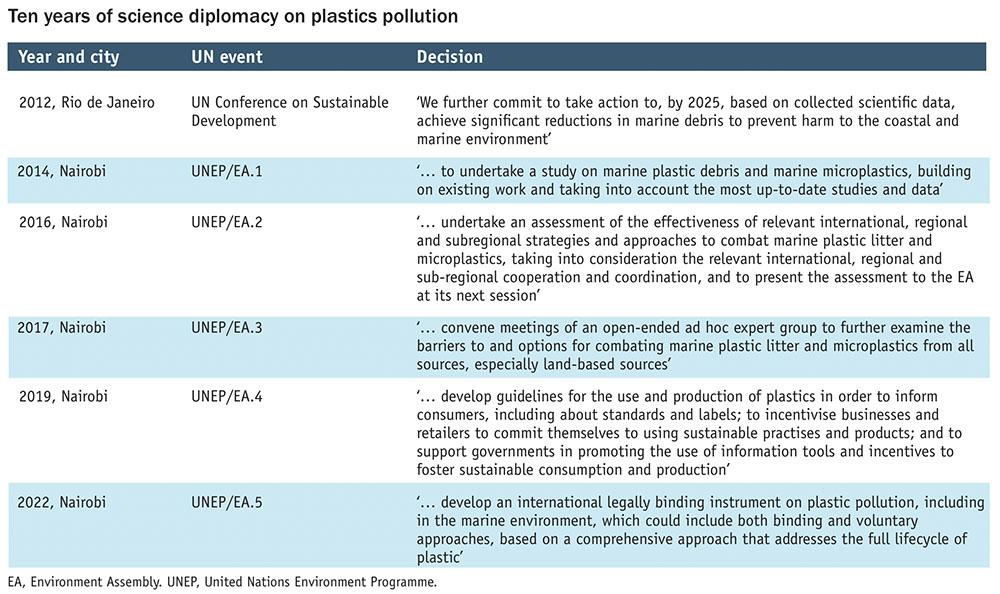

Plastics pollution was first noted as a problem by scientists in the 1960s and 1970s. By 2012, recognition of the problem had grown to the point that United Nations environment forums were making commitments to better understand and attempt to reduce marine debris. The United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) has made resolutions to address marine debris and plastic pollution at every meeting since its first meeting in 2014. Decisions through the UN are summarised in the table below.

In 2017, the third session of UNEA agreed to a resolution calling for the long-term elimination of all discharge of litter and microplastics to the ocean and established an intersessional

Ad Hoc Open-Ended Expert Group on Marine Litter and Microplastics (AHEG) to examine measures for combating marine plastic litter and microplastics from all sources, especially land-based sources. This group concluded in 2021 that the patchwork of binding and non-binding national and international measures was insufficient to address the problem, and presented a range of options, including establishing a new multilateral treaty.

The work of AHEG – a significant example of science diplomacy in action – was critical to building the momentum that culminated in March 2022, with the Australian Government and other Members of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) agreeing to establish an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to negotiate a new treaty on plastic pollution. The decision was made through the UNEA resolution ‘End plastic pollution: towards an international legally binding instrument’.

During these negotiations, Australia and others successfully advocated for a comprehensive mandate to address plastic pollution in all environments, covering the entire life cycle of plastics, and based on circular economy principles. This aligns with Australia’s domestic policies to build a circular economy for plastics.

Following UNEA 5.2, there was a special session to commemorate UNEP’s 50th birthday, where it was noted that in 1972 ‘the environment was a fringe issue’; however, now it is ever more central to global progress. A global science diplomacy process is underway – ‘on track for a cure’ to the plastic pollution challenge (UNEA-5 President Espen Barth Eide).

Commencing negotiations on a new treaty is vital, of course. But these will take several years to complete, and even more to implement. In the interim, industry, community groups, regional organisations, environment non-government organisations and Australian, state and territory and local governments are taking significant action to address plastic pollution. The connections between technical expertise and policy development that have resulted in action at the community and national level are a solid basis to build the science diplomacy that will occur through the work of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee negotiations.

The Australian Government has worked closely with industry and other key stakeholders to start building a circular economy for plastics, including through actions to minimise plastic waste through design, phase out unnecessary plastics and find alternatives, recover more from our waste streams, and invest in more facilities to repurpose our plastic waste.

CSIRO has established a whole-of-organisation mission to end plastic waste, with a goal of an 80% reduction in plastic waste entering the environment by 2030. Major research programs have been established across CSIRO, including for turning plastic waste into commodities, using the principles of the circular economy and supporting new industries based on what is now waste. Capability in chemistry, data science, materials and manufacturing will be employed to help build a more resilient manufacturing base in Australia.

Chemistry Australia, Australia’s national body representing Australia’s $40 billion chemical industry, has taken a leadership role, working with the community and governments to contribute to building a circular economy for plastics, including by establishing product stewardship initiatives.

Grassroots citizen science is also supporting innovative not-for-profit organisations to take action. Community not-for-profit groups such as Tangaroa Blue, Conservation Volunteers Australia, Keep Australia Beautiful and Clean Up Australia have been working directly on beaches and other environments around Australia, organising volunteers to clean up plastic pollution. These groups often work with Indigenous rangers in remote regions and have shown what a difference working together can make. Their work has allowed us to increase our understanding of what the waste is and where it is coming from, which is vital if we are to stop waste streams from entering the environment in the first place.

We are living through the development of a global response to plastic pollution, a response that started in the 1960s with environmental research and is now approaching the level of a global treaty. It is important that scientists and officials understand not only their part of the problem, either technical or diplomatic, but how to work with each other to develop practical, and implementable, policy and regulatory frameworks and technical solutions. It is important that our schools and universities relay these stories to inspire the next generation of committed individuals to meet the challenges of the future.

Many in RACI have contributed to solving this broad and complex problem. Often this has been by way of the many opportunities and channels that RACI provides for people to be informed and to come together. We need to continue to provide and to grasp these opportunities to contribute, personally and through our multiple organisations and networks so that we can improve our environment for all.

Further reading

Webb J.M., Spurling T.H., Simpson G.W. Chem. Aust. December 2020, p. 33; AsiaChem January 2021, pp. 114–18.

World Economic Forum (2016). The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics (weforum.org).

UNEP. Historic day in the campaign to beat plastic pollution: Nations commit to develop a legally binding agreement (unep.org).

International Union for Conservation of Nature. Issues Brief: Marine plastic pollution (iucn.org).

UNEA. UNEA-5.2: Major Step Toward A Comprehensive Plastics Treaty – A New Global Treaty On Plastic Pollution.