She must have been determined, ambitious and, above all, completely devoted to her family. This is a story of how Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleeva worked and dedicated tirelessly, sacrificing her health to give the maximum opportunity to her children, in particular her youngest, Dmitri.

Maria’s world

Maria (née Kornilyeva) was born into a successful merchant family in 1793 in the Russian city of Tobolsk, in eastern Siberia, at the confluence of the Ob and Irtysch rivers. Her mother died at her birth and she was raised by her father with the help of a nanny. As a girl, she was not able to attend school but was motivated enough to learn from the books and materials that her brother brought home from his school lessons. The family had also accumulated a large number of books, which she read. Later in her life, she would encourage all her children to read and to appreciate, as she put it, ‘the gift of words on paper’.

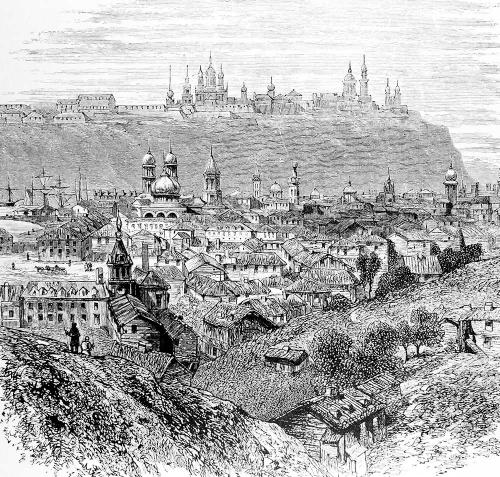

During this time, Tobolsk was the centre of the Russian Siberian province stretching from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, being its main military, administrative, political and religious centre. The Ural Mountains were seen as the natural divide between Europe and Asia, but the Tobolsk region had been extensively colonised by western Russians and it seems Maria’s family was mainly of this stock. Many sources, however, quote a family legend in which Maria’s grandfather married a ‘Tartar beauty’, whose death caused him to die of grief. The Tartars originated from the vast northern and central Asia landmass, also inhabited by other various Turco-Mongol semi-nomadic peoples.

This eastern expansion of the Russian empire had been initiated by Peter the Great, who had used Tobolsk as a springboard for the region’s development, and this was continued by subsequent rulers. The spectacular Tobolsk Kremlin (administrative centre) was built in 1800 and is known as the ‘pearl of Siberia’.

Ivan Mendeleev

In 1809, Maria married Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleev from the Tver province near Moscow. Ivan’s father was a Russian Orthodox priest, Pavel Maximovich Sokolov, who had four sons. As per the tradition for priests at the time, they all had different family names, with Ivan receiving the name of a neighbouring landlord, Mr Mendeleev. Ivan trained as a teacher at the St Petersburg Chief Pedagogical Institute, with his first assignment after graduating in 1807 being at the Tobolsk Classical Gymnasium; he became its director in 1828. In this context, a gymnasium was equivalent to a preparatory primary/high school with an emphasis on academic achievement, as a forerunner to university.

Newlyweds

Ivan and Maria set up house and home in Tobolsk, and according to Russian tradition she adopted the feminised version of her husband’s surname, usually done by adding an ‘a’, to become Maria Mendeleeva. The newlyweds were pious Russian Orthodox Christians and had 14–17 children (the exact number is disputed). Not all survived, which is not a surprise for that time, even without considering the harsh Siberian climate and its remoteness from medical facilities. All sources agree that the last, born in 1834, was a boy, Dmitri, with his middle name, according to Russian tradition, denoting he was the ‘son of’ Ivan. He was thus named Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev. He quickly became his mother’s favourite and she started putting money away for him at an early age.

It is interesting to note that Maria’s middle name was Dmitrievna, which by the above traditions means ‘daughter of Dmitri’. Most sources mention Maria’s father and grandfather as pioneers of the Tobolsk region, founding the region’s first glass factory and printing press and publishing the first newspaper in Siberia, the Irtysch. Maria admired her father’s drive to succeed and had perhaps also inherited it. In those days, as in other parts of the world, the lot and rights of women would have left much to be desired and her opportunities were limited. The next best thing, she may have thought, was to put all her efforts into the next generation, in particular her father’s namesake and her last child, born when she was 41.

Young Dmitri

Dmitri was home schooled by Maria until he was seven, after which he entered the Tobolsk Classical Gymnasium. Records show that Dmitri was not a great student, with many episodes of bad behaviour. The gymnasium appeared to be an intellectually limiting place, where the philosophy of the reigning monarch, Nicholas I, was promoted. This may not have agreed with young Dmitri’s more expansive preliminary education given to him by his mother. There was a heavy emphasis on the classics, Latin and German, which did not interest Dmitri, but he did well in mathematics, physics and the sciences. Maria must have been pleased with this; I can imagine her poring over Dmitri’s every school report. Little did young Dmitri know that his course was set; he would be given the utmost opportunity to excel in this field – but did he have what was needed to make the most of it?

Tragedies

The family suffered a series of tragedies shortly after Dmitri’s birth, with his father developing blindness due to cataracts and eventually retiring from the gymnasium. Maria was left to fend for the family and, not being able to support her children on the meagre government pension, took on the management of her family’s glass factory – about 27 kilometres outside Tobolsk in a village called Aremzianka – which had been inactive for some time. This would not have been an easy task for a woman then, although not unheard of in Siberia, where there was a history of ‘strong women’.

In this rural setting, the young Dmitri spent the first five years of his life and it is said that he was particularly interested in what would have appeared to be the wondrous transformation of earthy materials (e.g. sand and limestone) under the action of fierce fire to produce beautiful clear, coloured glasses. In later life, he would always have a picture of these glassworks on his office wall.

Ivan’s health continued to deteriorate, and he died in 1847. The family experienced more tragedy the following year when a fire burnt and destroyed the glass factory. After this, the family understandably fell on hard times. It does seem that in this stage of the family’s history, most of Maria’s children were no longer her responsibility, with only the two youngest in her care (Elizabeth and Dmitri). The situation did not deter her from executing her plans for Dmitri. He was now 15 years old and ready for the next step in his education: university.

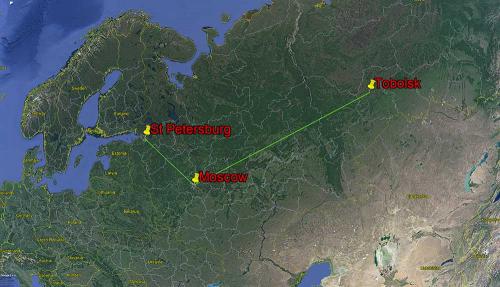

With the seat of Russian power centred in the west, Maria set her sights in that direction; she would take Dmitri to Moscow University, one of the finest in the land, and 2200 kilometres away. She would not waste any time: using the last of her money, and only a few months after the factory fire, she set upon her way. Perhaps she knew that she was running out of time.

Journeys

The year was 1849, well before highways and Russia’s first railway. Maria had travelled to Moscow and surrounds before in the early part of her marriage as Ivan assumed new teaching posts. One source quotes that she had once taken her ailing husband to Moscow for specialist medical advice. She also had a brother who lived there, so presumably she had a place to stay. Much has been made of this journey and perhaps it is over-romanticised, but to cross 2200 kilometres of what would have been then mostly bleak Siberian landscape, including traversing the Ural Mountains, in a state of poverty with two children in tow, would have taken a monumental effort.

Various sources give different methods for how she and her two children completed the journey: sleigh, horseback and walking. One source states that she hitchhiked a ride. Russian prerail technology for horse-drawn sleighs and carts/coaches was well advanced, so I suspect that this would’ve been the mode of transport, taking three to four weeks under normal conditions. Whatever transport was used, Maria’s determination to give Dmitri a university education drove her on.

Her long, arduous trip over, Maria reached Moscow and its famous university, only to be foiled by the ultimate insult: red tape. The university would not accept a student from Tobolsk, whose educational district fell into that of the local regional university. Maria thought that her brother’s connections could help, but the university administration would not budge. She must have been bitterly disappointed, and I suspect that there would have been a colourful discussion in the enrolments office of Moscow University that day.

Maria clearly wanted Dmitri to attend a recognised educational institution, not content with a lesser known regional university. The next best thing was St Petersburg University, which was 700 kilometres from Moscow and another week of travelling by horse and cart. Once again, she didn’t waste any time. The year after the Moscow trip, Maria and her two children endured the arduous journey to St Petersburg.

One source claims that, after reaching St Petersburg, she tried to get Dmitri enrolled in the great city’s university, but once again she was foiled. She had to settle for the Chief Pedagogical Institute, where Dmitri’s father had studied. The emphasis of the institute had since shifted from training teachers to independent research and was housed inside the University of St Petersburg. Studies were arranged in a number of streams, and Maria enrolled Dmitri in the physical–mathematical stream. Academics from the University often visited and gave lectures in the Institute – Dmitri thrived in this atmosphere and achieved good grades in his studies. He had successfully begun his career as a scientist.

It had been a tumultuous three years for Maria, and this took the ultimate toll – she died of tuberculosis in September 1850, the same year that Dmitri entered the Institute. She must have felt that she had done all that she could and now it was up to Dmitri. It is a great pity that she was not able to see the fruits of her labours and watch Dmitri flourish.

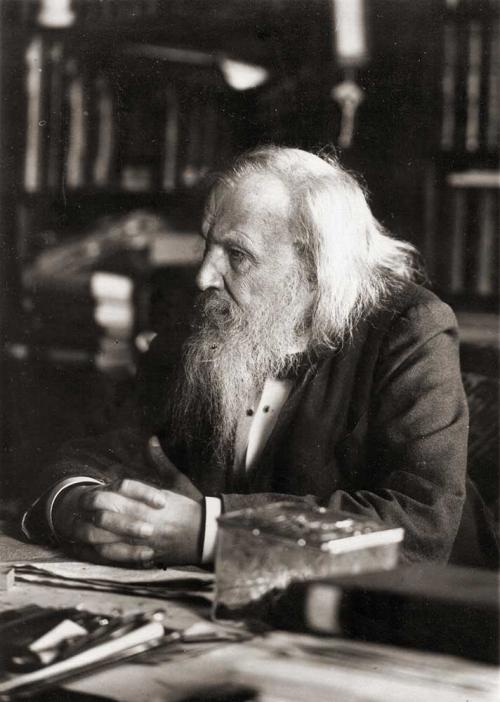

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev

After his beloved mother, and a few months later his sister, were taken by the scourge of tuberculosis, Dmitri was by himself in St Petersburg. He also contracted the disease, and despite a doctor’s prediction that ‘this one will not survive’, he miraculously did. He continued at the Institute, and took up chemistry as his area of study, completing his doctorate and visiting the laboratories of Kirchhoff and Bunsen. He also attended the watershed 1860 Karlsruhe Congress, where he heard the influential talk by Cannizzaro on atomic weights. As an academic, he wrote organic chemistry textbooks, perhaps reflecting his mother’s love of ‘words on paper’, which seemed to have coalesced all current knowledge and his experiences to get his mind ticking.

How Dmitri came up with the periodic table of the elements, and stood out among contemporaries with similar ideas to become a giant of science, is a great story for another time. He was well aware of what his mother had done for him. In 1887, as a Professor in Chemistry at the University of St Petersburg, he published a study on the property of solutions. It contained the following introduction:

This investigation is dedicated to the memory of a mother by her youngest offspring. Conducting a factory, she could educate him only by her own work. She instructed him by example, corrected with love, and in order to devote him to science she left Siberia with him, spending thus her last resources and strength. When dying, she said, ‘Refrain from illusions, insist on work, and not on words. Patiently search divine and scientific truth’.

Mendeleev’s study was published 18 years after his first draft of the periodic table (in 1869), of which we are celebrating the 150th anniversary this year. I imagine that at the time he was reflecting on his achievement of arranging the chemical elements known then and predicting new ones. Evidently, he was also thinking of his mother, with a wish to honour her love and fulfil the dreams she had for him.